|

Rogues on AOL

check out this piece for Asylum. Thanks to Jeremy Taylor for the piece.

it is also below with no images:

Mar 1st 2010 By Jeremy Taylor

Rogue taxidermy is A) What happens after Sarah Palin encounters a moose,or B) the creation of oddities, using traditional taxidermy materials and techniques.

If you guessed B), it's probably because you were looking at the photo to the left.

Robert Marbury, along with his partners Scott Bibus and Sarina Brewer coined the intriguing phrase in 2004, after they meet at an art exhibition in Minneapolis and realized they were doing similar work. Together, they formed the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists.

Read on to hear more about the place of roadkill and veganism in rogue taxidermy, and more pictures of strange beasts.

This morbid mounting is from Scott Bibus's collection.

"Scott's whole point is showing death in taxidermy," Marbury told Asylum. "This violates an unwritten rule in taxidermy that you don't show death and you don't show blood."

Road kill, such as squirrels, are a big part of the "recycled" philosophy of rogue taxidermy. According to Marbury, the best time collect these unfortunate critters is in October or November, when nature keeps the carcasses cool enough to prevent maggots, but not so cold as to freeze.

The first time Marbury did a show with Bibus and Brewer a dead squirrel was spotted on the road during setting up. "My two partners ran right over to it and fought over who would get it," Marbury remembered. "It eventually turned into a piece."

Here is a piece that eventually got the last laugh. (Sort of.)

Marbury didn't join his partners in their pursuit of the dead squirrel because considers himself a "vegan" taxidermist. As such, he uses taxidermy materials and stitching to fashion his beasts from recycled pelts of toy stuffed animals.

He does, however, participate in Masterclass/Gamefeeds. In these events, whatever animal the artist prepares for the exhibit is also made into food, which is then served to the audience.

"You're not killing an animal just for the work," Marbury explained. "You're using the animals to create a conversation about death and taxidermy."

Mixing different animals is also considered taboo in taxidermy. But it happens to be one of Sarina Brewer's specialties. This chimera, which Brewer calls Capricorn, is ready for the land, sea or air.

Like Bilbus and Marbury, Brewer also embraces a "recycled" approach to taxidermy, and, according to her Web site, "utilizes animals that are roadkill, discarded livestock, destroyed nuisance animals, casualties of the pet trade or animals that died of natural causes."

The Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists boasts a membership of about 40 artist from all over he world. New Zealander Lisa Black, who specializes in "fixed" creations, has an intriguing steam punk aesthetic to her work.

According to Marbury, anyone can practice basic taxidermy just by following the instruction you can find on sites such as taxidermy.net. Still, you're going to need a dead animal, a lot of space and, as Marbury puts it, "a really understanding spouse or roommate."

A collection of rogue taxidermy will be on display at La Luz De Jesus gallery in Los Angeles, from May 7–30.

2008.12.05 - 23.15 / 2008.12.06 - 03.00 : TRACKS

Rogue taxidermy

Imprimer

Envoyer à un ami

Les poubelles, fournisseurs officiels des "rogue taxidermists", les adeptes de l'empaillage plutôt tordu. Entre Tim Burton et Docteur Frankenstein, ces artistes donnent un sérieux coup de scalpel à l'art de la taxidermie!

LA TAXIDERMIE

À la Renaissance, les taxidermistes remplissent les cabinets de curiosités d’étranges chimères faites d'animaux assemblés, par jeu mais aussi pour refléter les croyances de l’époque en l’existence de créatures fantasmagoriques. Aujourd’hui, la taxidermie décalée part à l'assaut de l'art contemporain. Ces réalisations se vendent des fortunes comme le bestiaire hybride de Maurizio Cattelan avec ces animaux placés dans des situations inattendues. Mais c'est l'anglais Damien Hirst qui a touché le jackpot! La côte de ces bêtes coupées en deux puis conservées dans le formol atteint aujourd'hui les sommets de l'art contemporain.

NATE HILL ET SES CHINATOWN GARBAGE TOUR

Quand il quitte son job d'infirmier à l'hôpital, le new-yorkais Nate Hill adore dépecer et assembler des cadavres d'animaux pour créer des espèces inédites : c’est l’art de la rogue taxidermie ou "taxidermie tordue". Pour Nate, pas question d’empailler le chien de sa grand-mère pour lui faire un souvenir. La taxidermie, c’est pour lui un moyen d’inventer des créatures surnaturelles. Une fois par mois à la tombée de la nuit, Nate organise le Chinatown Garbage Tour dans le quartier chinois de New-York. Toute la soirée, les aficionados de la Rogue taxidermy font les poubelles des innombrables restaurants chinois du coin pour dénicher les bouts d’animaux jetés qui serviront de base à leurs œuvres. Chez les Rogue taxidermistes, très soucieux des droits des animaux, on ne tue pas les bêtes pour les empailler. Ça pue un peu, mais quel bonheur!

BONNIE WOOD - DU GLAMOUR ET DES CARCASSES

Norwich en Angleterre, Bonnie Wood immortalise ses animaux fétiches dans des postures religieuses.

Pour la jeune artiste anglaise Bonnie Wood, la rogue taxidermy, c’est l’art de faire du glamour avec des carcasses. Lapins aux allures d’icônes russes, bagues et broches serties de crânes de rat, elle vend sa drôle de collection sur internet. Maniaco-dépressive depuis l’adolescence, elle exorcise ses démons en donnant une autre vie aux animaux morts.

M.A.R.T

Comme Nate Hill, Bonnie Wood est membre de la M.A.R.T, la "Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists", un réseau international qui fait peu à peu son entrée dans les galeries d’art. Il promeut la taxidermie tordue via des concours et des remises de prix où se bousculent les apprentis Frankenstein et leurs monstres de tout poil.

LIZ MCGRATH

lisabeth Mc Grath a décidé d'inventer ex nihilo des créatures chimériques faites de matériaux synthétiques.

À Downtown Los Angeles, l’une des membres de la M.A.R.T vit de son art. Fan de taxidermie traditionnelle, Liz McGrath a été jusqu'à empailler son toutou qui trône désormais dans sa chambre. Quand elle ne chante pas dans Miss Derringer, un groupe rock de Los Angeles, Liz s’enferme des jours entiers dans son atelier. Exit les os et poils d’animaux, c’est avec des mannequins de mousse qu’elle assemble ses créatures : une cohorte de bestioles aux allures déglinguées, mi-jouets mi-démons à la Tim Burton. Des bestioles imaginaires nées dans la tête de cette fille de prêtre qui, lorsqu’elle avait 14 ans, a été internée par sa famille dans une maison de redressement ultra religieuse.

Extreme Taxidermy Art

By Rebecca Hurvitz

Oct 27, 2009, 13:15

real detroit weekly

Phone calls were made from the U.P. down to Ypsilanti, and there didn’t seem to be a taxidermist in Michigan that wanted to talk about their craft outside the traditional realm of hunting trophies. Lucky for RDW readers with a love of the bizarre, there are many taxidermists with the minds of mad scientists, the skills of fine artists and the guts (pun intended) to put this insight to work. “Most reputable taxidermists won’t even do novelty. It doesn’t represent the industry,” was the response of a taxidermist out of Midland. Well, that’s debatable.

One taxidermist with Michigan-roots who is stepping far out of the traditional box is Kate Clark. Clark, who received her MFA from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, produces thoughtprovoking and considerably eerie sculptures of wild animals with human faces using taxidermy practices. ”I begin by traditionally mounting the hide of the animal’s body. I then cut and stitch the leather skin of the animal’s face over soft clay, sculpting the features under the skin to create a smooth transition of animal body into human face," says Clark. "I pin along the stitching to hold the drying leather together, while also exaggerating the visible seams.” Clark, whose work is considered fine art and not simply novelty taxidermy, has shown her collections at The Detroit Artists’ Market and exhibits all over the country.

“If you look back before natural history museums, the custom of collecting animals was to secure oddities and rarities," explains Robert Marbury, one of the co-founders of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists (MART). "These cabinets of curiosities often had gaff pieces. The oldest gaff seems to be the Jenny Haniver. A more common one would be the FeeJee Mermaid, made famous by PT Barnum, or the Jackalope.” The term “novelty” in the world of taxidermy means kitsch to the max. Think squirrels sipping mini bottles of Corona or raccoon families in tiny birch-bark canoes. “Gaffs” are more mythical animals, like unicorns or two-headed goats.

Loba North, an artist and taxidermy enthusiast out of Minnesota, knows all too well how much people love dead animals posed into humorous positions. North is the administrator of the Livejournal.com community, WTF Taxidermy. This is a forum for people to post unique, funny or just downright awful examples of taxidermy. “It’s pretty normal for younger adults to buy things specifically because they are amusingly weird or tacky. It’s like seeing a movie that is 'so bad it’s good,'“ says North of the popularity of novelty taxidermy in younger generations. “A lot of the members [of WTF Taxidermy] are also members of [Fur, Hide, and Bone — North’s other LJ community], but then there are lots of people who don’t have a specific interest in taxidermy, they just want to laugh at the funny pictures and captions.” The internet certainly has become a medium not only for taxidermists to share their work, but also for outsiders to learn about animal art in its rarest forms. “I think the internet has increased people’s interest in natural history art. And like other areas of the internet, the extreme often gains more attention than the normal,” says Marbury. Novelty and gaff taxidermy, however, are just pit stops on the journey from traditional to bizarre.

North isn’t just a fan of kitsch, she’s first and foremost an artist who uses her appreciation for wildlife as inspiration for art made of animal materials. A surprising number of artists are producing art with taxidermy techniques. Marbury, along with MART co-founders Sarina Brewer and Scott Bibus, are artists taking taxidermy to the extreme.

And where does all this animal material come from? “For [MART], we ask that the animals be sourced through ethical channels. That would mean that the animal is not killed for the purpose of the piece. Some people use road kill, especially in the late fall when the road kill does not rot quickly. Animals can also come through the food industry, and there are a few people who have contacted me from farms that have an odd animal still-born,” explains Marbury. Marbury is actually a vegan taxidermist. His project, The Urban Beast Project, is a series of fictitious, hybrid animals, each with a story describing their evolutionary paths that allow them to exist (or become extinct) in urban settings. Co-founders Brewer and Bibus use actual animal material in their collections. Brewer’s work is a variety of curiosities including gaffs, novelty and even jewelry. Bibus’ collection is gruesome, grotesque and looks like it came right off of a horror film sound stage.

Past the bear skin rugs and mounted deer heads, there is a new generation of artists using animal material to evoke emotion, inspire reactions and make you think — and isn’t that what art is for afterall? | RDW

Artists breathe life into dead animal parts

Rogue taxidermy ruffles feathers, but has many fans

By MATHILDE PIARD and TOM DAVIS

MARCH 1, 2008

Shivering people dug through garbage bins outside Chinatown fishmarkets on a recent February night, hoping to scoop out a perfect-looking fin, claw or fishhead.

A few found the smell repulsive. The sight and feel of slimy, slippery frog intestines made others wince.

But the monthly "Garbage Tour" pressed on as 30 people kept pace with 30-year-old Nate Hill of Brooklyn as he hunted for scraps of discarded animal flesh. Each piece, Hill said, could become part of a taxidermy sculpture that takes the form of, in his words, a "freak animal."

On that cold night, Hill came up empty. Instead, he shared what he found with the eclectic group of writers, lab technicians, painters and an off-duty police officer. "This is a frog head – anybody want it?" Hill asked. "I have plenty."

Hill and others known as "rogue taxidermists" find something awe-inspiring about hunting for mangled roadkill or severed fish pieces in restaurant garbage bags and transforming them into works of art that, they say, give "new life" to dead animals.

When he first started his free tours in July, Hill was accompanied by three people – one of whom was a friend. Now he gets people from all walks of life – including self-described animal lovers – who either enjoy finding frog heads, or just get a kick out of watching others scrounge through plastic bags filled with fish heads

Hill and others said the practice that has drawn criticism from animal rights groups and conventional taxidermists makes them "feel like God" as they craft new figures such as "jackalopes," "nardogs," "mud bears" and "A Dead Animal Man," or ADAM, a human figure made of animal parts.

"It's an intimate thing to be with death," said Robert Marbury, a co-founder of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists, the most prominent national group of its kind which has 35 members and has its own website, roguetaxidermy.com "When you spend a lot of time with death, you create a different awareness."

Being "rogue" requires creativity and originality even if it defies the conventions of mainstream taxidermy, which centers on realistic representations of animals. The goal of taxidermists is to reproduce a life-like, three-dimensional representation of an animal for permanent display. In many cases, the actual skin is preserved and mounted.

Unlike conventional taxidermy – which seeks to maintain the animal’s original appearance – many rogue taxidermists craft new creatures that, in some cases, appear to be in imminent peril. One Web site, put together by Scott Bibus, shows chickens, deer and squirrels with their mouths and eyes pulled wide open, as though they’re in shock. What appears to be blood covers – or drips from – their mouths.

Indulging in the art, rogue taxidermists said, also means withstanding criticism from people who find their work distasteful, immoral and not very artful.

Greg Crain, executive director of the National Taxidermists Association, refuses to even call the rogue version "taxidermy."

"They're making a different animal," Crain said. "What we make belonged in the wild, and doesn't look phony or stuffed."

A video report on rogue taxidermy drew more than 600 comments on zootoo.com, a Web site focusing on animal issues. Most of the comments were negative, labeling the practice as "crude," "disgusting" and "weird.”

The report targeted Hill's ADAM project, a human-shaped sculpture sewn out of animal parts that were retrieved from Chinatown garbage bins and roadkill. The parts include pieces of chicken, conch, cow, crab, deer, dog, duck, eel, fish, frog, lobster, rabbit and shark.

The Minnesota association’s Web site boasted that Hill's public exhibit for ADAM "was all that he promised: stinky, packed and at least one vomiting visitor." That same site was selling a "ram's heart on stand" for $80 and a "skinned squirrel head fridge magnet" for $15.

"It's an embarrassment," said Andrew Page, director of the hunting division of the Humane Society of the United States. "Animals are not supposed to be used as a prop to be shown as some kind of freak show."

Rogue taxidermists said they're animal lovers, too. Unlike conventional taxidermists, they said, they don't kill animals to make exhibit parts.

If anything, rogue taxidermists said, they find beauty in what's normally discarded and hauled to the curb for a weekly garbage pick-up. They say they don't kill animals for their work but they recycle ones that are already dead.

"Seeing a creation makes you question the mental state of the person, but they are just trying to represent death," said Marbury, who has stuffed animals as part of his "Urban Beasts" project. His work, which is available at urbanbeast.com, attempts to document and exhibit the plight of wild and feral animals living in urban areas.

On Hill's February Chinatown trip, some of those who were curious left feeling sickened. "This is kind of pathetic," Bert Kupferman of Long Island City said as he watched the group dip their arms up to their elbows into full bags of trash.

But many others appeared to be fascinated.

Some even brought their dates to see Hill display some of his creations – a snake with a squirrel paw that was stored in a jar filled with rubbing alcohol – then embark on a late-night, four-stop trip in Chinatown.

Hill passed out rubber globes, though his own hands felt "frozen" as he picked through the ice-cold animal parts that filled up trash bags outside the fish markets.

"This is a trip," said one man as he watched Hill and others dig through the trash, and pull out a long string of intestines. "This is cool," said another man.

"I think you pay more attention to the anatomy of everything," said Justine Barry of Brooklyn. "So instead of having a fish tail that you ignore when it just sits on your plate at a restaurant when you order a whole fish, now you look at it more. You can see the beauty."

Thanks Mikita

Sub Rosa: Mixed Pickles

by Mikita Brottman

Close your eyes. Imagine the bits and pieces left on the floor of a slaughterhouse. Consider the by-products of a veterinary surgery. Now imagine this detritus being gathered up and stitched together by Norman Bates from Psycho. The result? A strangely beautiful and surreal art known by practitioners and devotees as Rogue Taxidermy.

Taxidermy, which literally means “arrangement of skin”, was a special craft developed to exhibit the many kinds of exotic animals and strange specimens brought back from far-flung parts of the world. It flourished in the 18th Century, when voyagers and explorers would collect the skulls and skins of little-known creatures to display in private Cabinets of Curiosity. Later, Natural History museums began using the technique to present lifelike dioramas of birds and beasts. More recently, artists like Damien Hirst and Joel-Peter Witkin have caused controversies with their use of “real” human and animal parts. But there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and taxidermy isn’t limited to the realm of galleries and museums: it’s also a traditional part of the sideshow. In this spirit, Rogue Taxidermists—generally independent artists whose work is too eclectic or lowbrow to cause much of a stir—“advocate the showmanship of oddities, espouse the belief in natural adaptation and mutation, and encourage the desire to create displays of curiosity.”

The movement began with three artists from Minnesota, and though there are now Rogue Taxidermists all over world, the main US-based collective works under the title of the original group, the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists, or MART. Queen of the bunch is Minneapolis-based Sarina Brewer, founder of Custom Creature Taxidermy, and creator of “outlandish reveries of fur and flesh.” Brewer creates fictional composite animals for discerning collectors and thoughtful connoisseurs. Her odd, hybrid sculptures bring to mind creatures from ancient myth, exotic beasts from travelers’ tales: devil-cats, unicorns, flying monkeys and three-headed squirrels. These unique mounts are beautifully creepy, alarmingly realistic, and, more often than not, ugly-adorable. They’re not cheap, but Brewer also offers pickled pets at pocket prices for those of lesser means: $12 buys you a skinned rabbit head, $15 a jar of small mammal hearts. By day, Ms. Brewer is a licensed taxidermist and does traditional work for museums and private collectors. Leftovers from her work are made into jewelry (necklaces and earrings from animal parts cost between $15 and $20 apiece), or sold unadorned: dried squirrel tails by the dozen; birds’ wings; cleaned skulls, and pickled feet.

Scott Bibus, the second founder member of MART, specializes in more grotesque and disturbing artworks featuring semi-skinned creatures depicted in bloody tableaux, which are perhaps inspired by his day job of making latex props for horror films and haunted houses. Current sculptures include “Siamese Frogs”, “Screaming Housecat”, “Roadkill Opposum” (teeming with maggots), “Anti-Trophy” (a poised, decapitated gull), and “Fox Face Platter”, a bloody still life that’s perhaps best left to the imagination. Many of his works depict animals that have survived various unnamed disasters; an eviscerated guinea-pig, a squirrel chewing on a human finger, a rat eating its own legs. Bibus is interested in the cultural disconnect whereby we gladly use animals for clothing and decoration, and yet flinch in horror at explicitly violent images. By removing the evidence of pain and slaughter, he suggests, an activity such as “sitting on a leather couch” perhaps allows us to “brush against the edge of a great fear.” This “great fear” is viscerally embodied by Bibus’s horribly magnificent sculptures, in which he inverts the usual process of taxidermy by discarding much of the carcass and posing the guts. The results are sublime, though definitely not suited for your grandma’s mantelpiece, unless your grandma happens to be a serial killer.

Third founder member Robert Marbury works with more familiar, less blood-curdling materials, turning ordinary stuffed toys into fantasy creatures of the imagination. Marbury’s Urban Beast Project involves recycling the skins of discarded teddy bears and other plush toys, and turning them into “feral relatives” of their cuddly kin, which are then displayed in community gardens, abandoned lots, or public trees. Some of the Urban Beasts are made purely for display, others appear to be designed as new forms of household pets. By using ordinary stuffed animals, Marbury demystifies the process of taxidermy, although his Urban Beasts resemble no biological genus or species except, perhaps, those discussed in the annals of cryptozoology.

Most rogue taxidermists have a formal art education, and may also be employed as sculptors, crafters, taxidermists or other kinds of artists, and often incorporate this more “legitimate” kind of work into their anomalous sculptures. For example, Miranda Winn makes colorful painted boxes, each decorated with a themed diorama; these boxes then become frames to display “recycled weasels, farmed snakes and articulated skeletons.” Dressmaker Monique Motil gussies up her dead things in homemade outfits, like pretty little dolls, and exhibits them as “sartorial creatures and other curious monstrosities.”

Animal lovers may find these sculptures distasteful and unpleasant to look at, but most Rogue Taxidemists consider themselves nature enthusiasts (many are vegans or vegetarians), and most see their work as a way of appreciating animals, and bringing them a new kind of life. Body parts are invariably acquired post mortem, either from salvaged roadkill, or through taxidermy supply companies, which trade in antlers, tails, teeth, claws, fur and wings. Other Rogue Taxidermists use offal from abbatoirs and slaughterhouses, or animals donated by vets after they’ve been “put to sleep”. These artists intuitively foreground what’s most disturbing about the process of taxidermy, which is the way it blurs the distinction between the living and the dead.

As with the embalming of human cadavers, or the plastinated bodies of Gunther von Hagens, these uncanny sculptures erode the boundaries commonly believed to divide living things from inanimate objects, bringing to mind childhood nightmares of zombies, voodoo dolls, and toys that come to life in the night. Of course, there’s an unsettling quality to everything that makes use of dead bodies, from primitive shrines, Nazi relics, talismans and fetishes, to shrunken heads and the preserved remains of saints. Rogue Taxidermy, however, does not pay homage to death so much as pay tribute to the overlooked detritus of the natural world, of which death is only a part.

The Stuffing Dreams Are Made Of

by Silke Tudor

November 14th, 2006 12:10 PM

Takeshi Yamada attended the Secret Science Club's recent Great Autumnal Taxidermy Get-Together at Union Hall wearing a tuxedo, a beret, and a pound of Mardi Gras beads—nearly the same outfit he wears when trawling Coney Island Creek for animal carcasses.

"Old tuxedos and suits are cheaper than blue jeans," says Yamada, hefting a long-handled fishing net over his shoulder as he trudges through the tall weeds, which hide homeless tent encampments along the creek's banks. "And they look better."

To keep his suits looking their best, Yamada hangs them in the shower of his humble Coney Island home. It pays off. Yamada looked like a star at the Union Hall competition, where he was awarded the title of grand champion. Never mind that the title was of his own choosing.

"Takeshi wanted to be called grand champion, so we called him grand champion," explains Robert Marbury, one of the founders of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermy (MART). He presided over the recent taxidermy contest as well as the accompanying master class and game feed. "It's pretty rare that someone like Takeshi, with such a full cosmology, just falls into your lap. And Takeshi's cosmos is very, very full."

Born out of the mythos of Coney Island, Yamada's present-day cosmos includes several six-foot-long Mongolian death worms; a pair of Fiji mermaids; a two-headed baby; a hairy trout; a seven-fingered hand; fossilized fairies; jackalope stew; a five-foot-long bloodsucking chupacabra; a 16th-century homunculus; a legion of samurai warriors trapped in the bodies of horseshoe crabs; a tiny marsh dragon; a coven of freakishly large, nuclear-radiated stag beetles from Bikini Atoll; and a furry mer-bunny, all of which are brought to life using old bones, shells, resin, origami, and bits and pieces of refuse, both inorganic and fleshy.

"In the East, abnormalities are not seen as shocking," explains Yamada as he slogs through a deep, soggy thicket behind a baseball field. "The freakish is not a bad thing. It can represent the mystery of the universe. An expression of divinity. A blessing."

He felt a bit differently when a tiny, horn-like tumor began to grow out of his finger after he moved to Coney Island.

"Shazam!" exclaims Yamada, as he often does. "I was like jackalope!"

Yamada was treated for the growth, but the cosmic joke was not lost on him.

"Dreamland once captured the imagination of the entire world," says Yamada, poking through a pile of partially burnt garbage under a canopy of dripping trees near Gravesend Bay. "Coney Island was bigger than Disney World. It was the Hollywood of the time. This was the center of the pleasure principle and the place where monsters were born. Then, it burnt down and everyone just forgot."

As a fortification against the modern weakness for remembering, Yamada has created a line of Coney Island–brand soup cans promising jackalope, spiny bullfrog, hairy trout, nekomata, and Fiji alligator flesh. The Osaka native also paints canvases—like the epic 4 x 6 foot Battle for Coney Island—which draws on the mythological nature of his new home. But mostly Yamada builds "gaffs," fanciful and fearsome "artifacts" that are a far cry from the messy, slapdash sideshow attractions of P.T. Barnum and his ilk.

Over the years, Yamada's work has been shown everywhere from the Louisiana State Museum in New Orleans, where his Mardi Gras paintings earned him a key to the city, to the Coney Island public library, where a 15-month-long exhibition is under way.

"On the midway, these are called gaffs; in galleries, they might be called art; in movies, special effects," says Yamada, adding a moldering baseball to the slimy fish skeleton already in his sack. "It doesn't matter. It is just what I do. There is no emotion or ego in it."

But there is preparation. When not searching the seashore, Yamada studies zoology and anatomy as well as history. No dragon skeleton in Yamada's collection will ever possess wings and front legs ("That just wouldn't happen in nature!") nor would its tail be too short to provide proper balance. His hairy trout, rather than being made of fur, possesses thousands of individual hairs glued down by hand. And the giant radiated stag beetles, fashioned from numerous horseshoe crab parts, are precise enough to make an entomologist drool.

While the perfect hairy trout is not everybody's idea of the Mona Lisa—Yamada has actually painted a two-headed version featuring his own face—to some, it's close.

"It's worth holding an event just to meet somebody like this," explains Marbury.

At the Union Hall event, curiosity seekers laughed along with MART's explanation of Union Hall's own "Rump Ape," a monkey-faced gaff created by stretching a deer hind over a mannequin head and adding eyes. (Traditionally, the deer anus is used as the monkey's mouth, but in uptight taxidermy parlance, the anus is referred to as a "vent.") The contest itself drew rare taxidermy, such as an anteater called a pangolin, as well as more prosaic fare, such as a poorly treated chicken and a set of dog testes floating in a jar. Classic crypto- taxidermy such as the wolperding—the German predecessor of the jackalope, made by combining a black pheasant and a rabbit with horns—stood alongside Nate Hill's disturbing "puppy-fish-snake" chimera and A.V. Jones's sidesplitting crash test pigeon on a plaque. Still, Yamada stood out—and not solely because his mer-bunny, a seafaring rabbit-seal puppet, started sniffing women inappropriately.

"The first thing that strikes you about Takeshi is that he is very committed to his art," says Marbury. "He takes it really seriously. The second thing is, he's a character."

Mer-bunny misbehavior aside, Yamada's artful Fiji mermaid garnered a squirrel-skull trophy, mounted on a refrigerator magnet, and a full membership to MART. While the night's trophies and titles were mostly delivered for laughs—like the "You're Friggin' Nuts" squirrel scrotum award—the invitation from MART was not proffered lightly.

"We could tell from the very first e-mail that he was going to be a very active member," says Marbury. "He's like the Great Gazoo. He just appeared out of nowhere and began telling us how it was going to be."

Scott Bibus gestures as he removes the skin from a chicken with the help of Serena Brewer during his taxidermy lesson on Saturday.Photograph by Dennis W. Ho

Taxidermist to hipsters: Stuff it!

By Dana Rubinstein

The Brooklyn Papers

A chic bar in Park Slope hosted a master class on how to mount dead animals.

Taxidermy, of course, is an activity more commonly associated with union halls upstate than with Union Hall, the bar on Union Street.

But at 5:30 pm last Saturday night, Scott Bibus, a member of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists, sat down at a long table in the pub’s trendy basement, for once church-like in its silence.

Bibus put his scalpel to the breast of a white-feathered chicken, and sliced it down the middle, all the way to its “vent,” an industry euphemism for anus.

Then he took his latex-gloved finger and inserted it into the carcass to begin separating its delicate skin from the “inner anatomy.”

Taxidermy is the craft of skinning an animal, preserving that skin, and then mounting it onto a form sculpted to represent the original animal body.

The Rogue Taxidermists use the traditional craft as an artistic medium. Bibus, for example, likes to make his finished specimens look ghoulishly dead, in contrast to the conventional practice of making dead animals look ghoulishly alive.

Sarina Brewer, who assisted Bibus in the master class, likes to make gaffes, or fake animals, by combining the body parts of different species. She’s the kind of person who would put antlers on a squirrel skin to create the legendary “jackalope.”

Like most members of the Association, Bibus and Brewer rely on road kill for their carcases. But the chicken was store-bought.

“Step one is skinning,” said Bibus, giving a play-by-play. “Remove the skin as intact as possible, with as few incisions as possible. Any meat left behind will shrivel and be plagued by bugs.”

As Bibus carefully removed the skin from the body (and lectured about diseases carried by dead animals, such as the leprosy carried by armadillos), audience members fired a barrage of questions.

“What’s the best way to preserve cat whiskers?” one person asked.

Mothballs in Tupperware.

“If you want to just preserve the bones, can you use maggots?” another would-be animal stuffer asked.

Beetle larvae work better.

These weren’t the questions of audience members who came merely to gawk. Clearly some had a pre-existing interest in taxidermy.

“I’m a real natural history enthusiast,” said Carrie Laben, a Bedford-Stuyvesant resident. “I like the freakish aspect of it, too. This is absolutely an art form.”

By now, the shimmering, inside-out chicken skin was trembling in Bibus’s hands like raspberry jelly. The room began to smell of raw poultry.

Bibus pulled out the esophagus and tongue, and cut through to the intestines. After a few more tweaks, Bibus announced, “And he’s skinned!”

Afterwards, there was the inevitable taxidermy contest, an experience that was, arguably, even more other-worldly than the master class.

Brooklynites converged on the makeshift stage with every manner of preserved animal body.

The competing specimens included a mounted chicken skeleton called Genus Nicoleais Richias, the testicles of a dog named Merlot preserved in a jar of rubbing alcohol, an Indonesian “tringaling,” and a naturally mummified rat.

But the top prizes went to a pair of squirrel testicles mounted on a plaque, a pigeon specimen, and two gaffes — a Fiji mermaid and a Coney Island “searabbit.”

Takeshi Yamada, the Coney Island artist who submitted the two gaffes sees taxidermy as an art form that brings its practitioners closer to nature and the divine.

“This is a three-dimensional illusion, in contrast to the two-dimensional illusion of painting, so it brings us one step closer to God,” said Yamada. “It’s also an expression of how to live better and connect with the environment.”

Bibus shares a similar view of the craft.

“It’s a way for me to get close to animals,” said Bibus. “I have a deep respect for the natural world.”

And so, apparently, do the good people of Park Slope, many of whom clamored to take home the leftover rooster meat. Not to mount, but to eat.

Nov 9 2006

Brooklyn Bar Infused With Eau de Dead Animal

From the neighborhood rag the Brooklyn Papers comes news of a very special instructional course in taxidermy, held at Park Slope's Union Hall bar:

At 5:30 pm last Saturday night, Scott Bibus, a member of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists, sat down at a long table in the pub's trendy basement, for once church-like in its silence.

Bibus put his scalpel to the breast of a white-feathered chicken, and sliced it down the middle, all the way to its "vent," an industry euphemism for anus.

Mmm, delicious. Bet that went well with the flatbread!

This + that: Rogues return

Rogues return

Rogues return

The Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermy folks got a great reception at the Great Autumnal Taxidermy Get Together in Brooklyn last weekend, reports co-founder Robert Marbury. He and fellow founders Scott Bibus and Sarina Brewer conducted a master class with a chicken they bought in Chinatown. So as to waste nothing, they also cooked the poultry. The idea, Marbury explained, is that "whatever you taxidermy, you serve as food" - in this case, chicken gumbo, although he considerately also whipped up a vegan gumbo for the herbivores in the full house of about 100. They also met some "wonderfully strange" people in the competition that followed the meal, including Takeshi Yamada, who entered a mermaid and a "Coney Island sea rabbit." The association also signed up two new members.

JUDY ARGINTEANU

er, its the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists and we are serving meat. still the event will rock your sock off

Beasts go wild on taxidermy night in a Brooklyn bar

By Emily Hulme

amNewYork Staff Writer

October 24, 2006, 5:33 PM EDT

Brooklyn bar Union Hall offers up your standard entertainment: music, comedians and author readings. But alongside this traditional fare, Union Hall has a few things you don't normally see in a bar: a bocce ball court, Secret Science Club lectures and, Wednesday nigh, it presents the second annual "A Very Carnivorous Night and Taxidermy Contest."

I"With our bar, we were trying to model it off the basement of a Masonic hall or a natural history museum kind of feel that an old private gentlemen's club would have maintained in the cellar," said Andrew Templar, co-owner of Union Hall, which opened three months ago.

Templer and his partner, Jim Carden, participated in last year's taxidermy event when it was held at Pete's Candy Store in Williamsburg. They took top honors with their rump ape, an imaginary creature like the jackalope, but "far, far creepier," Templar said.

Friends made it for them after their deer heads were stolen from their other bar, Floyd. "They take a wig dummy, a styrofoam head and they use some of the deer fur and they make a face, so it looks like a human face and then they use the tail to make beard, so it looks like the bust of a creepy Bigfoot head mounted on a piece of steel," Templar said.

This year, he and Carden are hosting the event with Margaret Mittelbach and Michael Crewdson, authors of the taxidermy-inspired "Carnivorous Nights: On the Trail of the Tasmanian Tiger." Templar estimates that there will be about 20 entries, pieces mostly inherited or found at flea markets and garage sales. In addition to the contest, the Minneapolis Association of Rogue Taxidermy (MART) will be on hand for a master class followed by a vegan game feed, a stew that can be made with game items (although, as it's vegan, the stew will be made with tofu).

'A Very Carnivorous Night' Union Hall; master class 5pm, contest 8pm; Free. 702 Union St, Fifth Ave, Park Slope, Brooklyn (2, 3, 4, 5, Q to Atlantic Ave; R to Union St; F to Fourth Ave) 718-638-4400

Goings On About Town

“GREAT AUTUMNAL TAXIDERMY GET-TOGETHER”

Last fall, in conjunction with the publication of their book “Carnivorous Nights: On the Trail of the Tasmanian Tiger,” the authors Margaret Mittelbach and Michael Crewdson organized a taxidermy contest at Pete’s Candy Store, a bar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. They’ve decided to do it again this year in a new location, with a few changes. Mittelbach and Crewdson will be hosting, and the judging of all things stuffed and preserved will be done by Dorian Devins, a radio producer with an interest in science, and Rob Marbury, of the Minneapolis Association of Rogue Taxidermy. Animals on display at last year’s event included a mongoose (entwined with a cobra), an armadillo (being used as a handbag), and a crow (dubbed Poe). The contest drew people from all over the metropolitan region, from employees of the Parks Department and the American Museum of Natural History to professional taxidermists and “various other types,” according to Devins, who participated. “I don’t know how they found out about it, but they all just showed up with their things.” (Union Hall, 702 Union St., Park Slope, Brooklyn. No tickets necessary. Oct. 28 at 8, with a master class and game tasting with a vegan option led by the M.A.R.T.’s Marbury, starting at 5. To sign up for the class, e-mail [email protected].)

This is a fantastic walk through reviwe of the Cryptozoology show up at Bates College. Makes you want to go to Vacationland and see it. Don't forget it will have it's day in the MiddleWest come October

Cryptozoology Show 06

The Cryptozoology show opened last night at Bates College in Lewsiton, ME. The press has started with a piece onAbsolute Arts website and really nice spread in the

Portland Press Hearld(unfortunately the photos were suppressed for the online version, because the images look great in print.

Jeffery Kalstrom reviews the 2006 Juxtapoz group show at Ox-op and Soovac. He gives us a nice quote:

"The “rogue taxidermy” of Scott Bibus, Sarina Brewer, and Robert Marbury is a world of its own. This whole new field of work is by turns festinating, delightful, sad, and funny and a titch nauseating."

Thanks Jeffery!

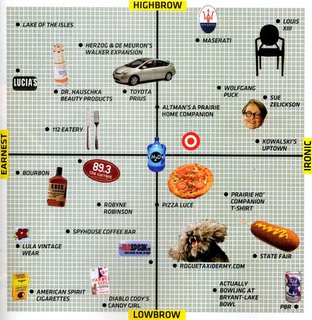

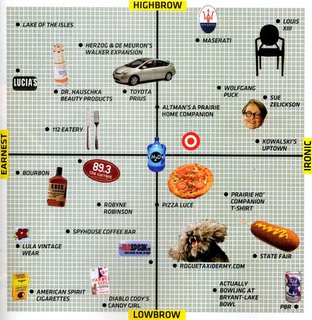

MART makes the Hipster guide of MSP Mag

If you have ever wondered where you place in a Hipsteronomics Graph, well, if you're with MART its somewhere near lowbrow and ironic. Thanks Steve Marsh and the people at Minneapolis/StPaul Magazine for thinking of us.

November 13, 2005

They're Soft and Cuddly, So Why Lash Them to the Front of a Truck?

By ANDY NEWMAN

A bear with a prominent grease spot on his little beige nose spends his days wedged behind the bumper guard of an ironworker's pickup in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn. A fuzzy rabbit and a clown, garroted by a bungee cord, slump from the front of a Dodge van in Park Slope. Stewie, the evil baby from "Family Guy," scowls from the grille of a Pepperidge Farm delivery truck in Brooklyn Heights, mold occasionally sprouting from his forehead.

All are soldiers in the tattered, scattered army of the stuffed: mostly discarded toys plucked from the trash and given new if punishing lives on the prows of large motor vehicles, their fluffy white guts flapping from burst seams and going gray in the soot-stream of a thousand exhaust pipes.

Grille-mounted stuffed animals form a compelling yet little-studied aspect of the urban streetscape, a traveling gallery of baldly transgressive public art. The time has come not just to praise them but to ask the big question. Why?

That is, why do a small percentage of trucks and vans have filthy plush toys lashed to their fronts, like prisoners at the mast? Are they someone's idea of a joke? Parking aids? Talismans against summonses?

Don't expect an easy answer.

Interviews with half a dozen truckers as well as folklorists, art historians and anthropologists revealed the grille-mounted plush toy to be a product of a tangle of physical circumstance, proximate and indirect influence, ethnic tradition, occupational mindset and Jungian archetype.

Like all adornments, of course, the grille pet advertises something about its owner. The very act of decorating a truck indicates an openness on the driver's part, according to Dan DiVittorio, owner of D & N Services, a carting company in Queens, and of a garbage truck with a squishy red skull on the front.

"It has to do something with their character," said Mr. DiVittorio, 27. "I don't see anybody that wouldn't be a halfway decent person putting something on their truck."

But a truck can be aesthetically modified in a million ways: "Mom" in spiffy gold letters across the hood; mudflaps depicting top-heavy women; flames painted along the sides. Why use beat-up stuffed animals?

One prevalent theory among truckers is that chicks dig them.

Robert Marbury, an artist who photographed dozens of Manhattan bumper fauna for a project in 2000 (see urbanbeast.com/faq/strapped.html), said he had once asked a trash hauler why he had a family of three mismatched bears strapped to his rig.

"He said: 'Yo, man, I drive a garbage truck. How am I going to get the ladies to look at me?' " Mr. Marbury recalled.

Mr. Marbury, who holds a degree in anthropology, added that the battered bear and his brethren had at least one foot in the vernacular cultures of Latin America, where the festive and the ghoulish enjoy a symbiotic relationship. Most of the drivers whose trucks he photographed were Hispanic, he said.

Monroe Denton, a lecturer in art history at the School of Visual Arts, traced the phenomenon's roots back to the figureheads that have animated bows of ships since the time of the pharaohs.

"There was some sort of heraldic device to deny the fact of this gigantic machine," he said. "You would have these humanizing forms, anthropomorphic forms - a device that both proclaims the identity of the machine and conceals it."

Whatever its origins, the grille-mounted cuddle object is found across the country. It has been spotted in Baltimore, Miami, Chicago and other cities.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, the artist in residence at New York City's Department of Sanitation, said that when she noticed the animals on garbagemen's trucks in the late 1970's, she "felt they were like these spirit creatures that were accompanying them on this endless journey in flux."

There are differences, though, between the dragon crowning a Viking ship - or, for that matter, the chrome bulldog guarding the hood of a Mack truck- and the scuzzy bunny bound to the bumper with rubber hose. The main one is that the grille-mounted stuffed animal is almost always a found object - "mongo," in garbageman's parlance. And in that respect it functions as a sort of trophy.

"I always felt," Ms. Ukeles said, "with these creatures that they withdrew from the garbage and refused to let go of, that there was an act of rescue involved."

That is certainly true for Julio Hernandez, a laborer for Aspen Tree Specialists in Brooklyn .

The GMC chipper-truck he rides in is graced with 11 figurines, each defective in one way or another - Hulk Hogan with both hands missing, a Frankenstein monster with a hole in his head, a nearly disintegrated black rubber rat. "People throw them out because they're broken," Mr. Hernandez, 38, said in Spanish. "They catch my attention."

A few months ago, Roberto Argueto spotted a floppy doll in the gutter near the headquarters of Sasco Construction in Brooklyn. The doll had brown pigtails, a white bonnet and the bluest eyes. He hung her from the front wall of the flatbed of his truck with a coat hanger, and he named her Margaret.

"I like the doll," said Mr. Argueto, 39. "She's pretty."

The flatbed carries some unforgiving payloads - scaffolding, bricks, sandbags - but Mr. Argueto protects Margaret.

"When I put something back there, I try to cover her," he said.

For all the reclaimed toys that are fussed over, though, there seem to be at least as many that are mistreated: tied to grilles in positions that recall the rack, and exposed to the maximum amount of road-salt and mud-spray.

Why do this? Whence the urge to debase an icon of innocence?

This is the true mystery of the grille-mounted stuffed animal, and it is here that the terrain gets heavily psychological and a bit murky.

Ms. Ukeles, who claims to understand sanitation workers fairly well, having shaken hands with 8,500 of them during a three-year performance project, said they identified on some level with their mascots.

"There's a transference in this," she said. "There's this soft, flesh-and-bone sanitation worker, who knows very well they could be crushed against this truck. The creature could be the sanitation worker in a very dangerous position, so the animal could be a stand-in."

(Stuffed animals, sadly, are verboten on city garbage trucks and nearly impossible to find these days; they were against department regulations even in the 1970's, but perhaps sanitation men are not the free spirits now that they were back then.)

At the same time, Ms. Ukeles said, the trucker, perhaps uncomfortable with his soft side, may feel compelled to punish it.

"Binding a soft thing to a very powerful truck - there's a kind of macho thing about that," she said.

That double identification with both victim and agent of violence may reflect the driver's frustrating position in society. Stuffed animals are found mostly on the trucks of men who perform hard, messy labor, which, despite the strength and bravery it demands, places them on the lower rungs of the ladder of occupational prestige.

The motley animal, then, can function as a badge of outsider status, a thumbed nose to the squares and suits. In that case, the cuter the mascot, the more meaningful its disintegration.

Thus, while Mr. DiVittorio, of the Queens carting company, is quite fond of the red plastic skull that adorns his garbage truck, he will never forget its predecessor, a three-foot-high stuffed Scooby Doo.

"Scooby was great," he recalled. "He covered the whole radiator and down to the bumper. You can't even imagine how many people took pictures of him."

Life on the road took its toll. "He got junked out riding in the front of the truck," Mr. DiVittorio said. "One of his arms was starting to fall off."

Mr. DiVittorio blamed the rivet-studded wire ties that held the dog fast. "You know how," he said, "if you have cuffs on your wrists, they dig into you?"

Eventually, Mr. DiVittorio said, Scooby's time came: "He went from the front of the truck to the back. We had to throw him away."

Scooby's story lends credence to the theory of Mr. Denton, the art historian, that the grille-mounted stuffed animal draws from the same well as the "abject art" movement that flourished in the 1990's and trafficked heavily in images of filth and of distressed bodies.

"That is part of the abject," he said, "this toy that is loved to death quite literally."

The externalization of an indoor object is another abject trope, Mr. Denton said. "An important aspect of the abject is the informe, the lack of boundaries," he said, using the French critical theory term, "the insides oozing out."

Charlie Maixner, a steamfitter for Deacon Corp. in Jericho on Long Island, has taken the informe to its logical extreme.

On the dashboard of his Econoline van is an adorable and pristine white bear, a gift from his 5-year-old daughter. But the bear is not for the outside world. On the grille is Mr. Hankey, salvaged from a chef's office during a kitchen renovation job.

Mr. Hankey, to the pop-culturally illiterate, appears to be a brown worm in a Santa hat. He is not. He is the carol-crooning excrement from "South Park," where he is formally known as Mr. Hankey the Christmas Poo.

"The bear on the dashboard, that's 'I love you, Daddy,' " Mr. Maixner said. "The other one is 'Daddy, what's that?' "

For that question, Mr. Maixner has a ready answer:

"I just tell her it's Mr. Hankey."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections XML Help Contact Us Work for Us Site Map Back to Top

Taxidermist has some unusual methods

by Matt Kelley

Some consider it a freak show. Others call it an offensive abomination of nature. But the man who organized a display of fanciful animals at Central College in Pella says it's just art. Robert Marbury is director of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists.

He says the exhibit includes oddities like a two-headed chick, a mermaid and a vampire squirrel in order to, in his words, give people a sense of awe and possibility at what nature has to offer. Marbury says "We are often creating animals that are mythological or animals that are unknown or undiscovered. When you look at them, the sort of hope for a lot of us is that, this sense of curiosity and wonder is going to fill you and you'll believe that really there is more to offer in the world than what we see day-to-day like our dogs and our cats."

The collection of creatures includes a "goth griffin" that has the body of a cat and the head of a crow. Marbury says the 20-member group includes a woman taxidermist who specializes in mythological beasts. Her Capricorn has the front of a goat, the tail of a fish and wings, giving the illusion it's all one real animal. She's also made a winged kitten, two-headed rats and something called a sea devil.

Marbury calls himself a "vegan taxidermist," saying his creatures are made entirely from recycled manufactured items, like old stuffed animals. Others in the group use "found objects" like roadkill or donated dead animals but they never kill an animal for their creations. He says another member of the group is more into making frightening creatures like killer deer and demonic dogs.

One of his pieces subverts the concept of the traditional food chain, depicting a beaver chewing on a human finger. Marbury says "It's really challenging and it's horrific but the issue is not to just simply offend. What we're really trying to do is really foster a conversation about what humans' role really is in the natural world." The display is at Central College's Mills Gallery through December 3rd. Or surf to "www.roguetaxidermy.com".

Misc.

Interview: Minnesota Association Of Rogue Taxidermists

posted by: Christopher Bahn

October 26, 2005 - 4:13am

With Halloween looming, it's an appropriate time to think about what makes a monster. Few know the answer better than Sarina Brewer, Scott Bibus, and Robert Marbury, the three artists at the core of the Minnesota Association Of Rogue Taxidermists, a Twin Cities art collective specializing in gore-drenched, provocative, and defiantly postmodern takes on the hunting-lodge staple. The three share a mordant sense of humor and a strong desire to poke holes in the boundaries between life and death, monstrous and normal. Bibus has a day job making zombies for a company that sells props and equipment for haunted houses. His work, typified by a squirrel gnawing on a bloody human finger, is the most cheerfully gory of the trio's. Brewer's self-termed "carcass art" also has plenty of dark wit, and evokes a strong sense of the uncanny. And Marbury creates fabric animals that are like rabid, nightmare versions of Muppets. The three gained national attention (including a rave in the New York Times) for their first group show last year. Roguetaxidermy.com features galleries of their art as well as the popular Beast Blender. The A.V. Club sat down with Marbury and Bibus (Brewer's roof collapsed, forcing her to cancel).

The A.V. Club: How do people react when they see your art for the first time?

Scott Bibus: We get a lot of people who are really upset initially, until you engage them. Part of our ethics charter says that one of our missions is to engage people who are offended about what we're doing and about the different issues that we're thinking about.

AVC: Your work can be so disturbing, it's probably important to note that you really do have an ethics charter.

SB: It's interesting. Me and Sarina, as the only two founding members who had to worry about ethics [because Marbury doesn't use taxidermy], our ethics charter is basically our practices from the beginning. We both are animal lovers. We don't want to hurt any animals. No animals that we use are killed for the purpose of mounting. That's like one of the biggest tenets: No animal must be killed because you want to make a piece of art. Like, "I want to make a possum. There's one! Bang! Now I got one!" The animals that are used in the art have to be procured through ethical means. Ethical for me includes buying them from a store, but that's only ethical because we as a society have decided to say this is a fine way to go about having an animal killed and then presented to you.

AVC: You have no way of knowing how the animal was treated.

SB: Well, you can almost guarantee yourself that it was treated very poorly.

AVC: Was your show at Creative Electric Studios last October your first one together as a group?

Robert Marbury: Originally, Dave [Salmela], who runs Creative Electric, wanted to do an Urban Beast show [Marbury's solo project]. And I had just met [Scott and Sarina] and I said, "Hey, why don't we think about doing this larger piece with the whole Rogue Taxidermy group." Dave's a vegetarian, and I think he thought, "Well, I don't know how I feel about that." But then he saw the work and got that gleam in his eye, like "I think this is gonna be great!"

SB: That was probably the busiest week of my life.

RM: [Laughs.] It was crazy!

AVC: Did you think the show would get such a large amount of attention, both positive and negative, as it did?

RM: Do other people consider it art? I think that we can say comfortably that as a concept it's worked. But at the time, we really had no idea how people were going to respond. As far as we were concerned that week, although we were putting a lot of work into it, we were the only ones that were going to appreciate it.

AVC: How close-knit is the working relationship between the three of you?

RM: Sarina has been the busiest of us all, and she's got a reputation independent of us—we all do in our own ways—and so it's been pretty cool also to come together and be very separate entities, but when it comes down to it, we all know we're trying to take care of each other.

SB: I think of it as a trio of musicians, so it's like the Rogue Taxidermy Trio, and we all have our solo albums. Sarina is like the rock star—her solo albums sell the best, you know. But we all have our different roles when we play in the trio.

RM: But as a group, and for what we created as a trio, [the national press coverage of the Creative Electric show] really was an enormous validation. There's no way around it. And then we just started getting these awesome responses. We started getting a lot of e-mails from people who were doing similar things and we came up with the idea of becoming a membership-based group. We still get ones—I got one this week—that say, "You're not artists. You're not talented, you're sick!"

SB: I send myself those e-mails every day. [Laughs.]

RM: One of the more fun things for us was people starting to offer up donations. A lot of them, we'd say, "No, thank you." Owls! We got a frozen owl! Totally illegal, please don't send that to us. This one guy who was in Texas or something, he wanted to send us some armadillos. But armadillos carry leprosy—they're the only other animals that do besides humans. So, no, thank you! Someone offered us human digits, and I turned them down. And my partners were like, "What? You turned them down?"

SB: Maybe it was some guy with leprosy, and that's why he was giving them away. [Laughs.] Who else would have spare fingers?

RM: What else were we offered?

SB: Well, I think the greatest thing is not the stuff we were offered, but the stuff we actually got. On the gallery doorsteps, somebody left a dead cat in a McDonald's bag. [Laughs.] And the gallery owner called me up, and I live right down the street, so I ran over there to get it.

AVC: So this is sort of your version of fan mail?

RM: [Laughs.] Yeah, total fan mail. We had an incredible network of eyes on the street, people on the street. This one woman called, and said, "I feel really bad, I just hit a squirrel on the corner of Hiawatha and 35! You've got to go get it." No, I'm doing something, I'm watching TV! Sarina at one point said, "If I get one more call telling me where there's a dead squirrel— what am I supposed to do? Drive around all day? My freezer is already full of stuff."

AVC: Where did you get the idea for the squirrel game feed you did at the Creative Electric show?

SB: The idea came from Pine City, where I went to taxidermy school. Three-quarters of the way through the year, they have a game feed. You take all the animals that you have taxidermied and have saved the meat from in preparation for this big day, and you cook it up and eat it. And you serve it to the public. They come in and you have a big buffet—elk stew, buffalo burgers, you know, all the animals in big crock pots. It's $8 a plate. People come in from the surrounding countryside and chow down and they're eating the animal and it's right there, looking at them, like, "How does it taste?" It was such a bizarre experience for me. I was born and raised in the city by totally anti-hunter parents, but I suppose for people who were raised in a rural situation it's not so strange. But that was one of the things that really got me thinking about taxidermy differently—it was strange for me to be eating an animal that I had seen butchered, which had never happened to me before. I had never experienced that process of consumption from its beginning to its end. I've always been interested in how I'm able to violate my own ethics, like I would be a vegetarian, ethically I'm all for that. I hate the corporate farming industry. I think it's disgusting. But I'm not a vegetarian—I eat meat all the time. One of the reasons I can do that is because when I go to the store, I don't have to be like, "One pig, please," and they hand me this squealing pig and I shoot it in the head and like, gut it. I don't have to do that. It comes in this neat little package that says, "ham." Mmm, ham. That tastes good. It's from the ham tree, probably.

AVC: Which is interesting, because from your art it seems like if anyone would be able to look death right in the face, it would be you.

SB: I don't know if I would if it was actually happening. I'm very sheepish, and couldn't imagine killing an animal. When I was a kid, I was remorseful for killing insects. I've always been interested in dead animals, but have always shirked away from violence of any sort.

AVC: What do you find interesting about dead animals?

SB: I honestly don't know. I like to say sometimes that for art, I think there's reasons and excuses and I have a lot of excuses and I don't know the reasons. I have a lot of stuff that when I'm making what I make, I think about—you know, "this is it." But really, I don't know. I've always been interested in dead animals and sick animals. I'm not sure.

AVC: Let's clarify the word "interested." When you say you're interested in them, how do you mean that?

SB: Maybe all kids are, in a way. It's one of those powerful memories from my childhood, like finding a dead fish on the side of a creek, and the poking with the stick, for me it wasn't like a casual poke, poke and then we ran away. It was a big thing for me. Maybe it's because I'm so far removed from animals that the only time I ever get to see them is butchered in a display case or dead. I've always been interested in them; it was like amateur biology. Fish by the creek side, I would be arrested by them, I would sit there and study them. It is just—very potent, powerful memories of dead raccoons that would come washing up on pond shores, hairless and white, and maybe just because they were out of the norm. I've never enjoyed idyllic countryside scenes; I think that's kind of boring. But if you add in a bloated, dead dog I find it very interesting. [Laughs.]

RM: That's for me the quote of the night. "If you add in a bloated, dead dog, then …" [Laughs.] Your dad's also a birder.

AVC: Did that train you to observe animals?

SB: Yeah—I mean, we are not a hunting family, but a big naturalistic family. My dad used to take us on nature walks all the time. We would spend a lot of time outdoors, fascinated by nature. And for me it wasn't confined to living nature. [Laughs.]

RM: We all have very funny relationships with our families. We all have very, very supportive families, and at the exhibition, Scott's folks came several times, and they would say, "Scott used to destroy all of our cookware. Did he tell you about the time that he cooked the turtle and the whole house stunk, and we had to throw the pot away?" And then my folks, they just think it's all funny, and they continue to give me ideas. I was thinking about making these large stuffed-animal ostriches, and my mom wrote me, "Oh, I can make you leg warmers!" Because she knits. "I'd love to make some leg warmers! Big, pink leg warmers! I've always wanted to be a part of your work, and now I can!"

AVC: So your families are OK with the macabre aspects of your work?

SB: My parents have learned to deal with it. I'm just starting to realize that I might be the black sheep of the family. I'd never thought of that. This is all pure aesthetics to me. I wasn't a troubled kid and I didn't mutilate animals. This is just something I'm aesthetically interested in. But in correspondence with other people, my parents have called me "original." And I think my grandmother actually said, "There's still hope!" [Laughs.] They've never been anything but supportive, but I am starting to realize that my position in the family may be something other than Golden Boy.

AVC: If a pet of yours died, would you use it in your work? Have you before?

SB: Not yet, but I am going to. I have an albino channel catfish—I used to work at a pet store and I brought it home one day because I thought it would look good with some other fish in this 55-gallon tank I had, and it was about four inches long. I knew they get kind of big… By the time it died, it was about two and a half feet. I still have that fish frozen. But with a pet, you've got to do something really cool. Part of me wants to just mount it as a traditional mount, with a little plaque, but I've never really thought of that as a really effective way of preserving the memory of an animal. If you have a dog that you love and you get it taxidermied, it's never going to be that dog. I can understand not wanting to let go of an animal that you've known and love for a long period of time… It's strange, especially if people believe that animals have souls, which I think a lot of serious pet owners do—they would never do that to a relative, but they're often people that talk about their animals as if they were relatives.

AVC: Do you think animals have souls?

SB: I don't know. That's a good question. I don't know if we have souls.

AVC: Are you familiar with Gunther von Hagens' Body Worlds, where he exhibits preserved and dissected human cadavers in lifelike poses?

SB: I'm fascinated by that whole thing, because I'm interested in a lot of Renaissance-era anatomy illustrations, when they used to show the body doing things. There's this museum in Italy called La Specola, which has these amazing wax reproductions. They'll have a lady laying languidly back, but her belly is open and you can see all her internal organs. But I think it irritates people now because we've moved so far away from that presentation of anatomy, because we want to remove anatomy from human existence. Anatomy textbooks now, they don't show faces, they certainly don't show personality, and there's no arranging. It's just, "Here's a close-up of this artery." But the Body Worlds art challenges that: Here's a person's muscular structure playing basketball. It's totally amazing, and people are very offended by it. They don't want to see it. We think of ourselves now that the Renaissance was a long time ago and we're much more enlightened. They were crazy! What did they do that mattered? Nothing! Just all the great art in the world. But our ideas of the human body are in a lot of ways a lot more backwards.

AVC: Would this art have been controversial back then?

SB: I don't think it would have been.

RM: You had these traveling shows [then]. … It's an interesting thing, looking at it from a contemporary frame, that we get a lot of people upset at us, but we're all very aware that it comes from a long, long history, and I think we all try to be pretty conscious and pretty clear in our references. Scott did a series of squirrels for our last show which were pretty funny, and a lot of them pointed directly to this La Specola museum's anatomy ideal that he just mentioned. One has a squirrel leaning back with his guts splayed open, but he looks pretty casual except for the fact that he's eviscerated. A woman we know who works at the [University of Minnesota's] Bell Museum and runs the Touch And See Room, she said for the most part she finds Scott's work hard, because she deals with so much of the side that you want people to conserve and protect. "However," she said, "I will never forget seeing the muskrat consuming his own feet, because that might be the happiest piece of taxidermy I've ever seen in my life."

SB: [Laughs.] He's just so happy to be eating those feet!

AVC: One of the most controversial aspects of the Body Worlds exhibit is that Von Hagens uses real human remains. Scott, you have a piece with a squirrel chewing on a human finger—what did you use? Was it a real finger?

SB: No, that's all fabricated. Not that I would decline the opportunity to use a real human finger, but using human body parts in your art requires a lot of effort. [Laughs.] And if there's one thing I am, it's a little bit lazy. You know, I'm not going to be, like, a Joel-Peter Witkin, who's going to have the cojones to march into a Mexican morgue and be like, "Gimme what you've got! I'm going to take it home," or to just sneak an arm into a pant leg and walk out with it.

AVC: Where do you draw the ethical line?

SB: You know, that's one of the things I've wrestled with. I'm a big serial killer buff. Ed Gein in particular. I actually don't find most of what he did wrong. The killing people—pretty wrong. But the digging up of the graves, I can't get myself to think that that's wrong. A little bit weird, yeah, it's a little weird. It's a lot weird. I guess what I'm saying is like, once somebody dies, and maybe this stems from my own feelings of emptiness and hopelessness about the end of life, but that there's nothing left of that person, and there's no reason that those remains should be revered, other than a symbol to a memory for some other people. If you're working with pets, if they're someone else's pets, if you were to get a donation from a veterinary place and it was somebody's dog, they might be very upset at what you did, and there's no reason to go upsetting people by flaunting the remains of their relatives and animals. But if that's not an issue, if no living person is going to be irritated by what you're doing and you're not causing anybody any harm, dig some graves! [Laughs.]

AVC: How do you feel about that, Rob?

RM: That's fantastic. I hope that's quoted. I can't wait for the e-mails.

SB: I think Rob's frightened. [Laughs.]

RM: I have feelings about the concept of revering the vessel or the body. And I understand the sentimental bit to it. I think we're starting to have a bigger discussion about big death, the industry of our remains. People make a crapload of money figuring out how to deal with our remains. There's something in that that becomes really perverse. It seems to me that on the scale of what we do as humans, we do a lot of perverse things, and to me the ones that are the least forgivable are the ones we do in society and we all go, "It's all OK." That's the stuff that I think requires us to make challenging work. I don't particularly think my own stuff is challenging, but as a group, I think it's good that people feel challenged by us. Cremating bodies is one thing, but embalming them and filling up land with bodies which you may have to dig up because they're so full of stuff—what are you going to do with them? But it is pretty fascinating to me that we get so worked up about how you're going to display a dead animal when what we do day-to-day creates a much more difficult world. Again, I think Big Death is the thing—how can you feel comfortable taking up so much land for your corpse, which is going to do very little for anybody? I know we want to leave a marker of who we are, and maybe my thoughts will change when I get older, but right now it seems pretty ridiculous.

AVC: If a burial in a cemetery is supposed to last forever, one day all the available land everywhere will be cemetery plots.

RM: Well, we can always hope for zombies.

SB: I'm hoping! [Laughs.]

AVC: So going back to the idea of where the boundaries lie for you: If Rob died, would you do something with his body if he said it was OK?

SB: Probably not. Would I do something with a human body? Yeah. Not Robert's, though, that'd be a little weird.

RM: I also wouldn't.

SB: It's a hard question to answer. Part of me says that maybe I would, because I do feel, to whatever degree that when I'm doing taxidermy I'm communing a little bit with an animal, not spiritually, just getting to know it. It feels intimate to me, and so there's something about it that would be tempting with somebody like my mom or dad. First of all you never probably hopefully see these people naked, I don't really want to, but you could unwrap them. [Laughs.] But presented with the actuality, it would probably be a whole different thing. It's so much work. People are so big and heavy! [Laughs.]

RM: Just remember that you've got my cell phone, so when you get arrested, just give me a call, I'll see what I can do. "You can unwrap 'em!"

SB: it'd be like a present on Christmas! [Laughs.] What I would do is, I'd do it to myself. If I were to lose a limb, I would taxidermy that. Any part of my body. Or if I ever have to have a part removed that cannot be preserved by taxidermy, I would like to keep it.

RM: Isn't that illegal, though?

SB: I think it is, I asked for my gallbladder when I got it taken out, and they said no. It made me mad.

RM: It's like, "This is mine!"

SB: I grew it! Little Beanie!

RM: It's funny, because Scott does predominantly taxidermy. But Sarina also does mummification, so she will use the skin and then she'll mummify the interior. And that's probably more disturbing to people. Scott's muskrat-eating-its-own-feet potentially had the ability to be the grossest thing in that show, but Sarina's carcass art really made people have a hard time. My favorite thing people would say was, "It stinks in here." And you'd be hard pressed to smell the difference. But our minds are so linked with death smelling a certain way.

AVC: Are you familiar with the "uncanny valley" theory of perception? It's the idea that a zombie or a badly rendered CGI character strikes us as particularly wrong or false, because the zombie looks very human but not human-looking enough to seem real, whereas a more stylized cartoon character or mannequin gives us enough psychological distance for us to be comfortable with it. It has to do with what you do and don't recognize as human. MART's work, collectively, seems to run along similar lines, crossing the boundary between the monstrous and the cute.

RM: Clowns. [Laughs.] It's true, and I think that's what's so fascinating to me about feralizing something. My biggest fear has always been coming upon someone in the house, and seeing their eyes. When I was on malaria medication, I had lots of very violent dreams, and most of them revolved around someone looking at you, and giving you this look, you know by seeing them, that they are fully committed to your destruction. Zombies. If all these zombies were walking around wearing Burger King masks, it probably wouldn't be scary.

Carmichael Lynch Tops Minneapolis Show

MINNEAPOLIS (October 14, 2005)— Carmichael Lynch led the creative charge at The 2005

Minneapolis Show, the Minnesota Ad Fed’s annual award program for the best in advertising and design

work (held Friday evening, October 14th at the Depot, Minneapolis).

Carmichael Lynch took Best of Show honors for an A.G. Edwards television spot called “Regardless,” a

part of CL’s broader “nest egg” campaign for the financial services company. CL also took the only Gold

awarded in the Interactive category for BeastBlender.com, created for the Rogue Taxidermy organization.

In all, CL took home 66 awards for its creative work for clients including Porsche, Harley-Davidson and

Gibson guitars.

It was created from the hands of a rogue taxidermist!

By Hunter Clauss

Assistant A&E Editor Columbia College Chronicle

Rogue taxidermists make no bones about how dead the subject is. In fact, for some rogue taxidermists, death is the main principle behind their art. The art form known as taxidermy began in the 1800s when hunters started bringing their trophies to upholstery shops, where the bodies would be stuffed with rags or cotton and sewn up, often with ghastly results.

More accurate techniques have since been developed, thanks to such innovators as Carl E. Akeley, who is sometimes referred to as the father of modern taxidermy. Akeley, who lived from 1864 to 1926, made two trips to Africa in his lifetime, and brought back the remains of many animals that helped in creating some of his most famous and revered mounts. His “Fighting African Elephants” can be found at the Field Musuem of Natural History, 1400 S. Michigan Ave., in the museum’s Stanley Field Hall, along with photographs from his trips to Africa.

Now, years after the death of Akeley, the art form is evolving again with the arrival of rogue taxidermy, which is sometimes called crypto-taxidermy. This form is like plain, good old-fashioned taxidermy in the sense that they both use dead animals to create an artistic depiction of wildlife. Traditional taxidermists, however, usually choose to display the subject in its natural environment, as if it were still alive. Rogue taxidermists, on the other hand, make no bones about how dead the subject is. In fact, for some rogue taxidermists, death is the main principle behind their art.

“It’s the animal in a traditional taxidermy pose, but it’s obviously dead,” said Scott Bibus, a rogue taxidermist. “Maybe its intestines are coming out, or it’s missing an arm or something that forces you to confront the idea that the animal you’re looking at is no longer alive.”

Bibus, 26, is the co-founder of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists along with his friends and fellow rogue taxidermists Serina Brewer and Robert Marbury. This up-and-coming organization has members from all over the United States and Canada and is dedicated to the timeless curiosity some have with the bizarre.

Whether it’s a fascination with animal mutations, such as a two-headed chicken, or of such sideshow classics as the Fiji mermaid—the mummified body of a mermaid creature that is half monkey and half fish—rogue taxidermists hope to entertain the imaginations of potential onlookers by taking taxidermy to a completely different level.